Temples in Japan usually request that you remove your shoes before entering, since shoes will tear up the woven grass tatami mats they use as flooring. In the USA and Canada, where they have carpets, that is not usually required. Sometimes other sects, such as the Zen school or Wats following the Thai tradition, will remove shoes as a gesture of respect. If you're visiting an unfamiliar Temple, wear clean socks.

Beyond that, there isn't usually much in the way of a dress code. In Chinese or Tibetan Temples where people bow all the way down, touching their forehead to a cushion or the floor respectively, you might not want to wear your kilt or a miniskirt. Not a problem in Shinshu temples.

When Buddhists meet, they traditionally greet each other in the way that was common in India and spread from there along with Buddhism- both hands held before the chest, palms together, fingers pointing upward at about 45 degrees. This is more common in other branches of Buddhism, but usually recognized in Shinshu, where we more often just shake hands.

Just outside the Temple there hangs a bronze gong that may weigh up to

200 lbs., called the "kansho", or "small bell". It is rung in a

traditional pattern to announce the start of the service- usually

slowly seven times, then a fast flutter slowing to a stately pace then

speeding up to a flutter again and fading out, slowly five times, the

fast-slow-fast bit again, then slowly three times, with the second a

bit softer and the last nice and loud. For funerals and memorial

services we use 2-5-3 instead of 7-5-3, and there is an attempt to

adopt a 3-3-3 pattern for weddings. Anyway, when you hear the bell, go

on inside. You can go in before if you like.

On

entering the Shrine room of the Temple, called the Hondo, you hold your

hands before you, palms together, with your Ojuzu (shown on the right)

around both sets of fingers but under the thumbs, tassels hanging down,

and bow from the waist, about 45 degrees, hold it for a second or two

then straighten up, then drop your hands. This bow is known as

"Gassho".

On

entering the Shrine room of the Temple, called the Hondo, you hold your

hands before you, palms together, with your Ojuzu (shown on the right)

around both sets of fingers but under the thumbs, tassels hanging down,

and bow from the waist, about 45 degrees, hold it for a second or two

then straighten up, then drop your hands. This bow is known as

"Gassho".

Often you will see a box by the door. This is for donations. In Chinese-tradition Temples, especially on holidays, the money is put into red envelopes first. But in Shin Temples, just drop it in. Or not. It's not required.

If

the incense has not been lit, take a seat (usually real pews- you don't

have to sit on the floor in Shin Temples!) and wait till it is. If (or

once) it is lit, walk up the center aisle to the front to incense

burner (shown to the left), wait your turn, then stop one pace from the

censer, gassho, and step forward with your left foot. Take a pinch of

the granular incense and toss it onto the burning charcoal or sticks of

incense inside the censer. Then gassho (hands together, 45 degrees),

step back on the right foot, bow (hands to your sides this time) and go

sit down. Watch it stepping backward- sometimes the kids don't give you

much room. If you arrive after the service has started, just sit down

and you can offer incense after the service is over. Both before and

after is good, too.

If

the incense has not been lit, take a seat (usually real pews- you don't

have to sit on the floor in Shin Temples!) and wait till it is. If (or

once) it is lit, walk up the center aisle to the front to incense

burner (shown to the left), wait your turn, then stop one pace from the

censer, gassho, and step forward with your left foot. Take a pinch of

the granular incense and toss it onto the burning charcoal or sticks of

incense inside the censer. Then gassho (hands together, 45 degrees),

step back on the right foot, bow (hands to your sides this time) and go

sit down. Watch it stepping backward- sometimes the kids don't give you

much room. If you arrive after the service has started, just sit down

and you can offer incense after the service is over. Both before and

after is good, too.

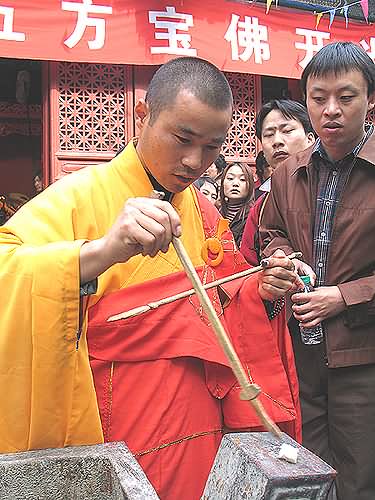

In Temples of Chinese tradition, the bowing is done differently. You go before the image of the Buddha, light a stick of incense (or, more often, three sticks), and stand them upright in the incense burner. There will be a mat or what looks like a footstool there. Stand facing the Buddha with the footstool in front of you, place your palms together as though you were about to do the Japanese "gassho", except with the hands held higher- about eye level is good. Then you kneel down with both palms and knees on the footstool (or mat), and touch the footstool with your forehead. At the moment your forehead touches, turn your palms upward (symbolizing your readiness to receive the Teachings) then stand, palms together and raised. Bow that way twice more for a total of three bows, but with the palms upward from the start. End with palms together, drop the hands, and leave. This should be acceptable at most Southeast Asian Temples.

In Shin services, we do a lot of standing up and sitting down. Chinese style Temples do even more, and commonly slowly parade around the room chanting. If you have problems with that, sit toward the rear and don't bother.

a simple Naijin

.a Chinese monk

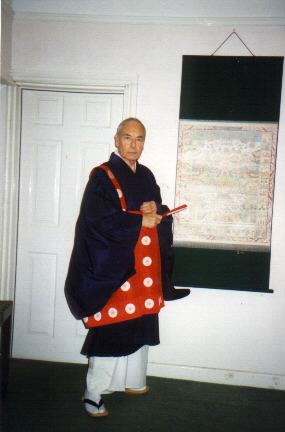

a minister in ordinary robes

.a minister in more formal robes

The raised portion in front is the Shrine, or Naijin in Japanese. The minister sits there and leads the chanting. There will almost always be a chairperson to lead the rest of the service, announcing what comes next and what page it's on. Most of it is in English, and the rest written in English letters so you can follow it. Even the Chinese-tradition Temples often have service books written in the English alphabet available for those who ask. The Shin minister is not a monk or nun. Many other Buddhist traditions are monastic, and the monks and nuns are not allowed to even touch members of the opposite sex. If the person presiding is wearing a red-orange robe or has a shaved head, this may apply. In Shin Temples, this is only a concern when there is a guest speaker from one of these other traditions. The Shin minister is usually called "Sensei" (pronounced "sin-say"), or by last name then Sensei, as "Tanaka-sensei". This last sounds awkward with European names, so instead of "Jones-sensei" we just say "Reverend Jones".

More terminology: The main thing chanted will be called a Sutra, which properly means a sermon spoken by the Buddha or by one of his followers in his presence and approved by him. Sometimes we chant verse portions of actual Sutras, sometimes commentaries or verses written by other famous Buddhist masters. Mostly they are intoned in a drone, and if you keep your eye on the page you can follow along. Don't worry if you can't. In some places, especially on holidays, the chairperson will start calling representatives of the Temple's affiliated groups, Boy Scouts &c., to offer incense during the Sutra chanting. There are also "gathas", which actually means "verses" and so applies more to some of the so-called "Sutras", but we use the term for songs, the equivalent of hymns.

You can find the printed versions of three of the most common chants, AND downloadable mp3 sound files for each of them here. They are the Junirai, the Juseige, and the Shoshinge.

At various points in the service, you will be invited to join in Nembutsu. Gassho (no need to stand, you can do it sitting) and while you are bent forward the leader will say "Namu Amida Butsu" (The Chinese pronounce it "Namo Omitofo"), then the Sangha (congregation) repeats it after him. This is done three times. Then bow a little more deeply and straighten up.

After the service, if there are children, there is usually "Dharma School" with a class for the adults. Otherwise there is often coffee and donuts or something, and you get a chance to meet people and ask questions.

The Japanese go to great lengths to keep you from feeling pressured, and to avoid embarrassing you by making a fuss about you. Unfortunately, to those of us brought up in non-Japanese traditions, this often feels like being given the cold shoulder. It's not. Don't give up.

At Home

An Obutsudan

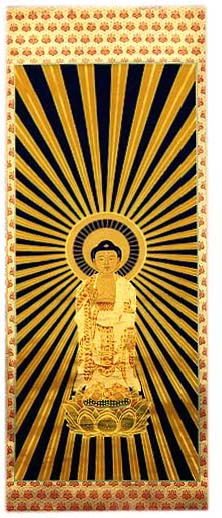

.a picture of Amida

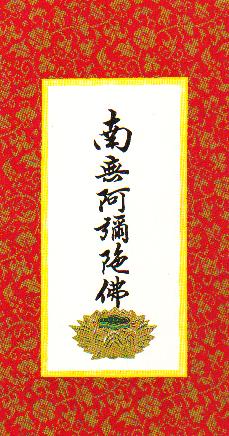

.the Nembutsu

a statue of Amida

.Shinran Shonin

The Obutsudan ("Honorable Buddha-place"), or more simply, Butsudan, is the home shrine. It has doors that are closed at night after the evening service and opened before the shorter morning service. The object of reverence is either a scroll with the written Japanese phrase "Namu Amida Butsu", a picture of Amida, or a statue of Amida- in that order of preference, according to Shinran Shonin, the founder of the sect. There are usually flowers, not just for prettiness- they symbolize impermanence. And exemplify it, so you don't always remove them as soon as they lose their first freshness. Pots of live flowers are good too, but artificial flowers are way down the list. Candles are traditional, lit at the beginning of the service and waved out with a fan or the hand, not blown out with the breath (considered impure), at the end, although many Obutsudans have electric lighting. There is commonly a small gong rung at the beginning, at the start and end of the Sutra, and at the close of the service.

The services are much the same as in the Temple. You gassho, offer incense, chant a Sutra and repeat the Nembutsu (the phrase "Namu Amida Butsu"), at the very least. In many other traditions, sticks of lit incense are stuck into the bowl, which is partly filled with rice to hold them up. The Japanese tradition is to light the stick incense and lay it flat in the bowl when preparing for the service, then sprinkle the powdered incense on top of it. If the incense burner is too small, break the sticks and lay the sections in a zig-zag pattern so that the burning section will light the next piece. You can also use a piece of burning charcoal instead. Favorite scents are wisteria (the crest shown above depicts two wisteria flowers.) and sandalwood. You can add other things to the order of service if you wish. Any of the things used in Temple services will do.

One other traditional practice I should mention: at the beginning of meals, people will bow, palms together (and, at religious events, holding the Ojuzu), and say "Itadakimasu" (pronounced "ee-tah-dah-kee-mas". The u at the end is silent) which means "I put it on top of my head". No kidding! It is a verbal substitute for bowing to the food, so that your head is lower than the food, and is an aid in feeling grateful for the food. You are supposed to thereby become more aware of the Buddhist teaching of Interdependence, of how all things interact and depend on causes, At Temple functions, this is usually led by the Chairperson or minister, and preceded by three Nembutsus. At home, I just say "I gratefully receive" or "I receive".

These are standard practices. Any given Temple may have variations that you will have to watch for, but this should get you started. If you have any questions, you can send me an e-mail. Good luck!